FN

255: Introduction to MNT

Teresa (Snyder) McFerran, MS, RD

Health Professions Division

Lane Community College

Eugene, Oregon

Unit 1 Preparations, Chapter 1

Nutrition and Health: Overview

Unit 1 Orientation

Quiz DUE before midnight (11:55 pm) SUNDAY, October

6th

Unit 1 Study

Questions DUE before midnight (11:55 pm) SUNDAY, October

6th

WELCOME to FN 255! Although

this is a fully on-line class, and we will not be meeting

face-to-face during the term, I want you to know that my goal is

to guide you through this course as if I were sitting right next

to you. If questions or concerns come up please take a deep breath

and re-read the material, and maybe skim the Syllabus, before

allowing yourself to become flustered. Once you have taken a deep

breath and re-read the material please consider re-starting your

computer (if this applies) or taking a short five-minute break. If

you are still confused feel free to contact me through our Moodle

messaging system or post your question(s) in our weekly forum. I

would highly encourage you not to wait until the last minute to

submit assignments so you have ample time to resolve any possible

road bumps that may arise. Best wishes and I look forward to

getting to know you as the term unfolds!

UNIT OBJECTIVES

After reading the assigned reading, filling out the Orientation

Quiz Questions, filling out the Unit 1 Outline, participating in

the "Forum Week 1", and

completing the Orientation Quiz AND Unit 1

Study Questions on Moodle, you will be able to:

- Know how this course is organized and where to find the

activities and assignments for each week.

- Communicate with other students in this class and gain

confidence to in our online learning environment.

- Discover due dates for activities in this class, plan

your time commitment accordingly, and set yourself up for

success in this class.

- Define the term "medical nutrition therapy" and

understand some of the common settings where MNT takes place.

- Understand the impact of cultural influences on nutrition

and the importance of cultural competency.

- Review some of the basic principles of nutrition in order

to be able to set MNT goals for a variety of health conditions

throughout the term.

RESOURCES

- Unit 1

Preparations (this document)

- Mosby's Pocket Guide

Series Nutrition Assessment and Care, Ch 1: Nutrition & Health

pp. 3-40

- Reading Calendar (above Week 1 in Moodle)

- Syllabus (above Week 1 in Moodle)

- Merriam webster medical dictionary: http://www.merriam-webster.com/

(select "medical")

- Please use the online medical dictionary to look up any

terminology you may not understand as you are reading the

text.

WEEKLY FORUMS:

Each week, there will be a FORUM that will allow you to post any questions you have about the

lecture or materials covered as well as allow the instructor to

post any changes or corrections

that need to be communicated.

A study question will ask if you participated at least once in this week's

forum BEFORE Friday at 5pm. (Refer the syllabus for additional

details and note that starting next week two forum postings

are required each week.)

FORUM WEEK 1: (Go to our

Moodle classroom and click on "Forum Week 1" to participate.)

- "Introductions": Briefly introduce yourself by

telling us were you grew up, what subject you are studying,

and briefly explain anything about your life right now you'd

like to share, such as your major/career goals,

hobbies/interests, etc. Make sure to include how long it has

been since taking either FN 225 or 105 and what prompted you

to enroll for this course.

-

"Student Questions": Do you have any questions

about the Unit 1

Preparations? Please post your questions/concerns in the

forum for others to be able to respond.

- "Online Success": Since this is an online class,

without a defined time for lecture, it may be a challenge to

find time during your busy week to complete the Unit

Preparations, Case Studies, and SQ (Study Questions). How will

you find a routine time, if you think that's important? If

you've taken an online class before, what wisdom can you

share? If this is your first online class what are your

fears/concerns and how have you already started overcoming

them?

-

"Cultural Competency": Based on the list of ways

in which you can seek out opportunities to develop

culturally competent skills in the Unit Preparations this

week, what ideas seems most practical for you to develop at

this time?

- "Health": How do you personally define the word

"health" or "healthy"? The Word Health Organization (WHO)

defines health as a "state of complete mental, physical, and

social well-being, not merely the absence of disease or

infirmity". How is this definition similar and different than

your definition for health?

-

CORRECTIONS / CLARIFICATIONS: (Please check our weekly

forum for additional corrections and clarifications.)

Notice what your syllabus says in the "Editing Profile" section

for disabling your email

address if you would rather not get messages in

your personal email regarding this class.

Unit 1 Preparations, Chapter 1

Nutrition and Health: Overview

Print and

complete Unit 1 Outline

in Moodle while you are viewing Unit 1 Preparations (this

document) online.

Unlike the Orientation Quiz questions above, the Unit Study

Questions will be based on the answers you obtain from filling

in ALL of the blanks in your outline and checking out the

links for the Unit 1 Preparations below. In other words, you

will not

receive a copy of the actual SQ (study questions). Filling out

the unit preparations outline is the best way to prepare for

the SQ, and considering all quizzes are timed, you will not

have ample time to complete the quiz if the Unit Preparations

are not completed first.

The following topics will be covered this week:

I. Medical Nutrition

Therapy Defined

II.

Cultural Influences on Nutrition and Cultural Competency

III. Nutrition Review

IV. Chapter 1: Nutrition & Health Overview

I.

Medical Nutrition Therapy Defined

Considering the title of this class is Introduction to Medical

Nutrition Therapy, it's important that you can define the term

medical nutrition therapy. The following are a few definitions:

-

Page 281 of our Mosby text states that "acute and

chronic illnesses are treated in a variety of settings,

including acute care hospitals, rehabilitation centers,

extended care facilities, clinics, offices of private

practitioners, and patient's homes. Whatever the setting,

however, nutrition care is an essential part of treatment.

In recognition of its importance, assessment, planning, and

nutrition care of medical, surgical, and emotional

conditions are referred to as medical nutrition therapy."

-

A textbook commonly used by nutrition majors when

studying MNT defines medical nutrition therapy as "the use

of specific nutrition interventions to treat an illness,

injury, or condition" (Krause's food, nutrition and diet

therapy, 11th edn, L.K. Mahan, S. Escott-Stump, p. 496).

-

The Academy

of Nutrition and Dietetics, or AND, defines MNT as

“nutritional diagnostic, therapy, and counseling services

for the purpose of disease management which are furnished by

a registered dietitian or nutrition professional...” (source

Medicare MNT legislation, 2000). MNT is a specific

application of the Nutrition Care Process in clinical

settings that is focused on the management of diseases. MNT

involves in-depth individualized nutrition assessment and a

duration and frequency of care using the Nutrition Care

Process to manage disease.

-

The Centers

for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS, recognizes

that "nutrition and diet play an important role in helping

people with certain diseases manage their health. For people

with diabetes or renal diseases, proper

diet and nutrition can help prevent and reduce complications

from their conditions. Medicare covers medical nutrition

therapy services for people with diabetes or renal diseases

to help them manage their conditions."

Considering CMS provides coverage for MNT for people with certain

diseases, it seems pertinent to recap the ten leading causes of

death in the U.S. (causes in bold indicate that the cause of death

is related to nutrition):

* Heart

disease

* Cancers

* Strokes

* Chronic lung disease

* Accidents

* Diabetes

mellitus

* Pneumonia and influenza

* Alzheimer's disease

* Kidney disease

* Blood infections

II. Cultural

Influences on Nutrition and Cultural Competency

Some of the commonly cited reasons for needing

culturally competent health care individuals include the

following:

- demographic diversity and projected population shifts

- increased utilization of traditional therapies

- disparities in health status of various racial/ethnic

groups

- under representation of health care providers from

diverse backgrounds

Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines culture as "... the integrated pattern of human

knowledge, belief, and behavior that depends upon man's capacity

for learning and transmitting knowledge to succeeding

generations." Therefore, culture is not something we are born

with, but rather it is learned and passed on from one generation

to the next. Culture encompasses more than simply race or

ethnicity because it is a shared system of values, beliefs,

attitudes, and learned behaviors. For example, dress, family

structure, language, and food habits often indicate one's culture.

Below are a few pictures that were taken while my colleague's

husband lived in Japan. The first picture shows the traditional

attire that is worn for kyudo, or Japanese archery. The second

picture was taken at the end of a tea ceremony, or chakai, and the

women are all adored in kimonos. The next picture is of me taking

shodo or calligraphy lessons in Japan, and the last picture is of

dango, which are Japanese dumpling made from rice flour and is

often served with green tea.

Every decade a census of the United States is conducted. According

to the U.S. Census 2010, 308.7 million people live in the United

States. The categories used in the most recent census included

white, black or African American, American Indian and Alaska

Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, and

"some other 'race.'" Most of the respondents who answered

"some other race" were Hispanic or Latino. Note: Clearly, there

are many subgroups within each of these categories.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, "between 2000 and

2010, the Hispanic population grew by 43 percent, rising from 35.3

million in 2000 to 50.5 million in 2010. The rise in the Hispanic

population accounted for more than half of the 27.3 million

increase in the total U.S. population."

The expected changes in the nation's demographic makeup in race

and age categories have been cited numerous times as reason enough

for health professionals to pursue personal competence in cultural

knowledge. It is projected that by 2050 Latinos will triple to become the largest

minority group and the percentage of Asians will nearly double. By 2065 Non-Hispanic

whites will most likely be a minority

group.

The table below shows the approximate distribution of

race/ethnicity of the overall U.S. population, based on the 2010

U.S. Census:

Race/Ethnicity

|

% of U.S.

Population, 2010

|

White

|

72%

|

Hispanic or Latino

|

16%

|

| Black or African

American |

12%

|

Asian

|

5%

|

American Indian and

Alaskan Native

|

<1%

|

Native Hawaian/Other

Pacific Islander

|

<1%

|

2010 U.S. Census data

The U.S. Census Bureau website 2010, American Community Survey,

includes a breakdown of the demographic characteristics of Lane

County, Oregon:

POPULATION OF Lane County: In 2010, Lane County had a total

population of 351,715. Fifty-one percent were female and 49

percent were male. The median age was 39 years. Twenty percent of

the population was under 18 years and 15 percent was 65 years and

older.

Please go to the following link (http://factfinder.census.gov/)

and enter Lane County, Oregon. Based on the information, answer

the questions in your Outline.

Many agree that the US population is currently more like a "salad bowl" rather than a

"melting pot." A salad may contain many ingredients, and blend

into a harmonious whole, but each ingredient retains its unique

taste and texture.

However, it is not enough to simply recognize and accept that our

culture continues to diversify. Cultural

competency, especially in healthcare, is the ability to

understand and respond effectively to the cultural and linguistic

needs of patients or clients. Implied is the acceptance and

tolerance of different backgrounds and their associated traits,

beliefs, etc., and absence of prejudice against unfamiliar

cultures. Learning to value diversity and being open-minded about

other cultures are key characteristics of cultural competency. A

culturally competent professional recognizes and understands the

differences in his or her culture and the culture of the patient

or client. Therefore, it is no wonder that cultural competency is

a current buzzword in health care.

Cultural competency is a process

that occurs along a continuum. At one end of the continuum is

cultural destructiveness and at the other end is cultural

proficiency. The chart below was developed by the National Center

for Cultural Competence in 1999.

According to the University of Michigan Health System, the steps

involved in developing personal cultural competency are as

follows:

- Recognize your own personal cultural biases and

preconceived ideas/opinions;

- Desire to learn about and become involved with people

from diverse cultures;

- Seek out and increase your knowledge about other

cultures; and

- Learn and develop multicultural communication and

counseling skills.

Along this journey to attain cultural proficiency, it is

important to understand the difference between stereotyping and

generalizations. Stereotyping

is an assumption that ALL people in a particular group think and

behave alike. Stereotypes are often judgmental and do not allow

for individual differences--for this reason, a stereotype is an ending point. For example, a

stereotype could be that "All white southerners eat pork, have

buttered grits for breakfast, and drink sugared tea." In contrast,

generalizations refer to

the trends or behaviors within a group, but with the knowledge

that further information is needed to determine if the

generalization applies to this particular person. Therefore,

a generalization is a starting

point. An example of a generalization-based questions is asking a

Jewish client "Do you follow traditional Jewish dietary laws?"

This question provides a starting point to work from rather than

stereotyping that all Jewish clients follow traditional dietary

laws.

Keep in mind that just as individuals within a cultural group are

unique, so are their diets. For example, not all

Japanese-Americans like wasabi. Thus the emphasis should be on

seeing the patient or client as an individual, which is also known as

patient-centered care. Providing patient-centered care can prevent

bias, prejudice, and stereotyping on the part of healthcare

providers from contributing to differences or disparities in care.

After all, the connection with the patient or client is the most important component.

According to the National Center for Cultural Competence, cultural

competency in healthcare is paramount for fostering more favorable

clinical outcomes, results in positive and rewarding interpersonal

experiences, and promotes patient or client satisfaction. In order

for health care to be successful, services must be received and

accepted. The real benefit of cultural competency is improved

outcomes. Cultural competency is NOT an optional skill to learn,

but rather a necessity.

In order to deliver culturally competent care, health care

providers should understand: beliefs, values, traditions and

practices of a person's culture, family structure and the roles

within the family in making decisions, health-related needs of

individuals, families, and communities, cultural beliefs about

health and etiology of diseases, cultural beliefs about healing

and disease treatments, and attitudes about seeking help from

health care providers.

The dominant American cultural paradigm is largely derived from

Anglo-American heritage and places high value on individualism,

privacy, personal responsibility and control. The "culture" of

healthcare in the U.S. reflects Anglo-American values, many of

which include being time oriented, focused on disease management

and treatment, and dedicated to preserving life at any cost. These

values are often in direct opposition of the values of many

traditional cultures, which often believe that fate, God or other

supernatural factors determines a person's destiny and directly

influences their health and family almost always includes extended

family, who commonly participate in the decision-making,

especially regarding health care.

When my colleague, Amber, was a dietetic intern, which means

she had completed her Bachelor's degree in nutrition but was

required to complete a one-year internship and pass a national

exam before she could use the title of Registered Dietitian,

she interned at a hospital where about 70% of the patients

were Vietnamese. She covered the cardiac unit, and the first

nutrition education that she provided was with a patient who

primarily spoke Vietnamese. The nurse was their translator as

she was from Vietnam. The nurse was kind enough to let Amber

know that when giving dietary instructions it would be

perceived as disrespectful to give the instructions without

the family present. Amber agreed to return when the family was

present.

Like language, food

distinguishes one culture from another. A culture is strongly

identified with its foods, and it's food preferences will out last nearly any other

cultural practice. After all, what could be more culturally

defining and also unifying than diet? Persons of all cultures

today expect space to be made for their cultural norms, and

individuals who accept the United States as their new home,

although they may adopt U.S. portion sizes and fast-food culture,

typically maintain many of their own cultural food practices. In

order to positively impact the diet and health of a person or

family from another culture, one must understand their culture,

their communication style, values, and health beliefs. By

understanding these cultural aspects institutional food services

can work on including a variety of ethnic foods that are

reflective of their client base and nutrition counseling

interactions can incorporate familiar cultural foods.

The images below were taken at Papa's Soul Food Kitchen BBQ in

Eugene, OR. The menu includes foods some Americans would consider

to be unique or strange, such as jerk chicken, southern fried

snapper, collard greens, black-eyed peas, and sweet tea.

A good starting point for learning about cultural, ethnic and

religious food customs is to be able to access the nutritional

composition of many traditional foods.

A handy resource is the Oldways

Preservation Trust website. The mission of Oldways is an

internationally-respected non-profit, changing the way people eat

through practical and positive programs grounded in science,

traditions, and delicious foods and drinks. It is best known for

developing consumer-friendly health-promotion tools, including the

well-known Mediterranean Diet Pyramid.

The Mediterranean, Latino, African, Asian,

and Vegetarian diet pyramids can be found on the Oldways

website.

The packet will ask you a few questions that will require you to

check out the Heritage Food Guide Pyramids in the link above.

Starting next week, Week 2, you will analyze the nutritional

status of individuals from different racial, ethnic, and/or

religious group and life cycle stages. The cuisines that will be

discussed for each racial, ethnic, and/or religious group will

include the following:

- Vegetarian cuisine

- Food customs of religious cultures

- Native North American Indian cuisine

- Japanese cuisine

- Asian Indian cuisine

- Southeast Asian cuisine

- Chinese cuisine

- Soul food

- and potentially Caribbean cuisine

Based on what we've discussed about the importance of cultural

competence we all must continually seek out opportunities to

develop culturally competent skills. Some of the ways in which you

can do this are listed below:

- Explore the media. Read books, magazines, and newspaper

articles, and explore Web sites. Watch movies, videos and

television programs that pertain to other cultures and are

ideally targeted toward immigrant groups and non-native

speakers.

- Arrange cultural encounters. Attend fairs and religious

events. Go to restaurants and ethnic markets. Look for

opportunities to socialize with individuals from the target

culture.

- Take a walk down the grocery store's "ethnic foods" aisle

for a cursory lesson in diet diversity or visit local "ethnic

food" markets.

- Seek information on acceptable behaviors, courtesies,

customs, and expectations from a cultural expert that can help

you prepare for interactions and interpret actions.

- Walk or drive through communities to identify where

people gather, what types of stores and restaurants are

available, what is being advertised in windows, and how often

you hear the native language spoken.

- Visit community organizations to learn about a particular

cultural group, such as schools, block associations, senior

citizen's groups, and women's clubs.

- Many cultural groups have Web sites were you may find

chat rooms, advertisements, marriage brokers, lists of mail

order places for ethnic foods, and descriptive information

about food practices.

- Attend professional development and training classes or

group discussions.

- Take language lessons.

- Travel.

Below are a few images taken at a Japanese-American Lantern

Festival in Eugene, Oregon.

One consequence of not attaining cultural competency can be seen

in the multitude of healthcare

disparities that exist in the United States. A healthcare

disparity occurs when a segment of the population bears a

disproportionate incidence of a health condition or illness. A

segment of the population can include gender, race, ethnicity,

education or income, disability, living in rural localities, or

sexual orientation.

In the U.S. there are four historically under-represented people

groups, African Americans, Native Americans/American Indians,

Latinos, and Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders. (Sound familiar to

the categories used in the most recent census?) In general, there

is a higher incidence of certain cancers, cardiovascular disease,

diabetes, obesity, and mortality in these population groups

compared to non-Hispanic whites.

The following list includes some of the most common causes of

healthcare disparities in the U.S.

- socioeconomic status (lower education and income levels)

- lack of insurance

- culture

- access to and utilization of quality health care services

- discrimination, racism, and/or stereotyping

- physical environment (e.g. housing conditions)

The following is an example of a healthcare disparity:

- English-proficient Hispanics were about 50% more likely

to report receiving advice on physical activity, as compared

with limited English-proficient Hispanics, after controlling

for health insurance coverage and number of visits to a

physician during the last year. Sex, age, region of residence,

level of education, annual family income, and smoking status

were not significantly associated with receiving physical

activity and/or dietary advice (Limited English Proficiency Is a Barrier to Receipt

of Advice about Physical Activity and Diet among Hispanics

with Chronic Diseases in the United States by

Lopez-Quintero C., Berry E.M., Neumark Y., JADA, October

2009, 109:10, Pages 1769-1774).

Unfortunately, in today's fast paced life the health care

system is not immune to time pressures. The Institute of Medicine,

in its report Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and

Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, cast a spotlight on

time pressure in the clinical setting to eliminate stereotyping

and other uncertainties that could have a negative effect on

quality of care. “In the process of care, health professionals

must come to judgments about patients’ conditions and make

decisions about treatment, often without complete and accurate

information. In most cases, they must do so under severe time

pressure and resource constraints... [leading to] those factors

identified by social psychologists as likely to produce negative

outcomes due to lack of information, to stereotypes, and to

biases.”

The Office of Minority Health of the US Department of Health and

Human Services (HHS), in conjunction with the Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality, established National

Standards

on Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services

(CLAS), a collection of 14 mandates, guidelines, and

recommendations designed to eliminate racial and ethnic health

disparities. The idea behind the CLAS system is that better

communication leads to better adherence to medications and

lifestyle changes, which leads to improved health status, which

leads to less use of emergent care services and less frequent

hospitalizations

III. Nutrition Review

This week we will spend some time reviewing the basic principles

of nutrition. It might be helpful to dust off your FN 225 and/or

FN 105 notes and textbook, if you still have them, especially if

it's been awhile since you've taken the course. Don't forget to read chapter 1 of your textbook

this week too, which will provide you with a nutrition and health

overview. (Note that since your textbook was published in

2009, the sections related to Healthy People 2010,

Dietary Guidelines 2005, and MyPyramid are now Healthy People

2020, Dietary Guidelines 2010, and MyPlate. I have included

updated information in the lecture below.)

A. Health and Healthy People

The World Health Organization

(WHO) defines health as a "state

of complete physical, mental and social well-being, not merely

the absence of disease or infirmity."

Healthy People 2020 comprises the

Nation's comprehensive health objectives and stresses the need

to provide culturally competent, community-based health care

systems in order to address health disparities among different

segments of the population. Healthy People 2020 is considered to be

a health curriculum for the nation.

The "Overarching Goals" of Healthy

People 2020:

- Attain

high-quality, longer lives free of preventable disease,

disability, injury, and premature death.

- Achieve health

equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of

all groups.

- Create social and

physical environments that promote good health for all.

- Promote quality

of life, healthy development, and healthy behaviors

across all life stages.

B. From Dietary Reference Intakes to

MyPlate

-

DRI (Dietary

Reference Intakes): umbrella term for four possible

values that set nutrient intake standards for people

living in the U.S. and Canada (Dietitians commonly use DRI values when

determining the estimated needs of the patients they are

assessing, such as how many grams of protein one needs

per day. DRIs are also used for menu planning and

analyzing 24 hour recall data to prevent over or under

nutrition.)

-

Dietary Guidelines

for Americans 2010 and MyPlate are tools that help us translate scientific

research into everyday food choices.

C. Food Labels

-

DV- Daily

Value: food labels do NOT use the DRI values, but a

separate set of suggested daily intakes of calories and

selected nutrients (*We are going to say that the "magic"

%Daily Value is 10%.

In other words, we will consider a food a good source of a

nutrient if it has 10% or greater of the DV for that

nutrient per serving.*)

- If you need some additional resources to answer the

questions below check out the following links:

- Remember the following energy-yielding nutrients

(macronutrients) and their calorie content:

- Carbohydrates: 4 calories

per

gram

- Protein: 4 calories

per

gram

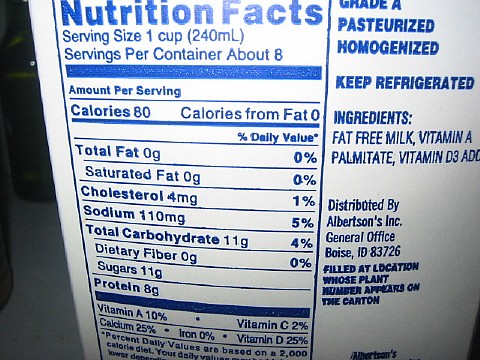

Use the food label image

above to answer the questions in your outline.

IV.

Chapter

1: Nutrition & Health Overview

Read Chapter 1

in your textbook and answer the questions in your outline.

Choose one of the online nutrition resources

below and answer the questions in your outline.

End of Week 1 Unit Preparations

After filling in ALL of the blanks to the

questions in your outline, go to the "Unit 1 Study

Questions" under Week 1 in Moodle to submit your answers.

(Note: If you take the

quiz after the due date, please send me a message. It will

probably not

be graded

until you do that as I

may not realize it was done. I can do this ONE time.)